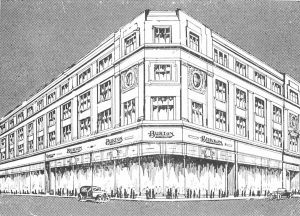

Hull (1936)

Montague Burton began to build new shops – ‘modern temples of commerce’ – around 1923, when he had amassed around 200 branches. The next year the company opened in a wing of Woolworth’s new superstore in Liverpool where Burton’s architect, Harry Wilson, worked alongside Woolworth’s William Priddle.

Liverpool (Church Street, 1924; from Ideals in Industry, 1936)

Early drawings of Woolworth’s Liverpool and London superstores, dated 1922-24, show that Woolworth intended to allocate space to billiard halls, but these never materialised. Instead, the idea of combining billiards and retailing was adopted by Burton.

Colchester, c.1930 (c. Historic England Archive

At this time Burton’s shops occupied a motley portfolio of leased buildings. They often had a striking appearance, with gigantic lettering plastered over their frontages – even screening upper-floor windows – with the invitation: ‘Let Montague Burton the Tailor of Taste Dress You’. The shopfronts followed a template. Each had a arched fascia of green glass, edged with gold and filled with white lettering. Below this ornate transom lights, still in the Edwardian fashion, displayed the words ‘Elegance’, ‘Taste’, ‘Economy’ and ‘Courtesy’. The entrance lobbies had mosaic floors.

Hessle Road, Hull, 1920s (c. Arcadia Group PLC)

More modern shopfront designs were adopted in the mid-1920s. At Liverpool (1924, see above), Hammersmith, Bradford (1925) and other branches of this period the transom lights were rectangular, punctuated by garlands and containing the usual words: ‘Courtesy’, ‘Taste’, etc. By the end of the decade, however, this had been superseded by the Burton ‘chain of merit’ (see below).

Nottingham (Beastmarket, 1924)

The Nottingham branch (Beastmarket, 1924) is typical of the earliest purpose-built Burton stores, having strong neo-Classical features and paired pilasters. From 1927 until 1929, when Burton went public, the shops were purchased and held by Burton’s property company, Key Estates Ltd. The estate agents Healey & Baker were employed to find suitable sites in prominent locations, ideally occupying corners. Unsurprisingly, many pubs were acquired. Sites were inspected by Burton’s Deputy Manager, Archibald W. Wansbrough (1880-1961), or by Montague Burton himself. Often the vendor was kept in the dark about Burton’s interest – in case this inflated the price.

Belfast, rebuilt after a fire in 1928.

Harry Wilson had become the company architect by the early 1920s, and was responsible for developing Burton’s house style. Montague Burton, however, maintained a close personal interest. The company’s in-house Architects Department was set up around 1932 under Wilson. He was followed as chief architect around 1937 by Nathaniel Martin, who was still in post in the early 1950s. The architects worked hand-in-hand with Burton’s Shopfitting and Building Departments, who coordinated the work of selected contractors. Throughout the late 1920s and 1930s they were kept phenomenally busy: by 1939 many of Burton’s 595 stores were purpose-built.

Douglas, Isle of Man (1929; Burmantofts white faience)

Burton’s buildings are instantly recognisable. However, they were not identical. It is sometimes said that Burton adopted four different designs: in fact the company’s buildings were much more varied than that. Façades, for example, could be clad in a variety of materials, including Portland or ‘Empire’ stone, emerald pearl granite, white faience (glazed terracotta) or red brick. Sometimes locally quarried sandstone was used, for example in Carlisle and Dundee.

Paisley (1929-30; listed Grade B)

Architecturally, façades were conceived as giant elevations, of the type made popular by Selfridges on Oxford Street in London in the years before the Great War. An example is the six-storey flagship store on the corner of Tottenham Court Road and New Oxford Street in London (1930), which was advertised as ‘the largest tailoring establishment in the world’.

Corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road (1930).

Set between the upper-floor pilasters of these stores were metal-framed windows with margin lights, and moulded metal spandrel panels which masked floor levels. The rendering was often classical – sometimes with strong Grecian overtones – but from the late 1920s this relatively ‘correct’ architectural approach was sidelined.

Bournemouth

Burton became one of the most enthusiastic exponents of the art deco style on British high streets: the armature of the buildings remained similar, but pilasters were replaced by moulded or ornamented fins (for example at Bury St Edmunds in 1933), while capitals were superseded by geometric blocks, or even stylised elephant heads (for example at Weston-super-Mare in 1932). The repertoire of motifs was extensive.

Bury St Edmunds (1933)

Weston-Super-Mare (1932)

Birmingham, Dale Road (1937)

Hitchin (1938) (photo: R. Baxter)

In the late 1930s a number of buildings, especially in historic town centres such as Woking, York, Truro and Hitchin (1938), were designed with more conservative neo-Georgian fronts. These were usually faced in red brick, with pale ashlar dressings and Ionic pilasters. Regardless of style, parapets added height to Burton’s buildings, but many of these were removed or rebuilt in later years because they became structurally unstable. Even if parapets survive, ‘Burton’ lettering has often ‘gone for a Burton’.

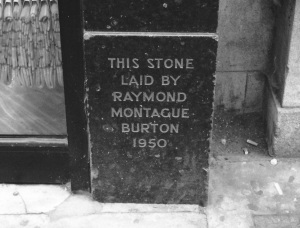

Two types of shopfront were used by Burton through the 1930s. They had two principal features in common. First, emerald granite frames with date stones laid by members of the Burton family. Second, transom lights displaying the company ‘chain of merit’: naming towns which hosted important branches. One design involved elongated hexagons and the other chevrons: motifs which were repeated on the entrance doors. Examples of both designs have survived, together with some of Burton’s lettered mosaic floors and entrance lobbies. Burton’s principal shopfitters were John Curtis Shopfitters of Leeds and the Cheltenham Shopfitting Co.

Abergavenny (1937)

Despite the imposing size of Burton’s buildings, only a small area was needed for each shop. An entrance screen of timber and glass gave a club-like sense of privacy. Inside was an uncluttered, masculine space. The floor was of oak block and the walls were lined by wooden mantle cases for hanging garments and fixtures for displaying rolls of cloth. Part of Burton’s buildings often contained lock-up shops. These were on short leases so that Burton could repossess the space if needed, for example when ready-to-wear departments opened in the mid-to-late 1930s.

Don Bradman and fellow cricketers in Burton’s, c.1933. (Ideals in Industry, 1936)

Montague Burton liked the first floors of his buildings to be used as temperance billiard halls. The space was designed with this in mind. Six-inch concrete floors were covered in wood block, and independent access was provided to one side of Burton’s shop. Some upper floors, for example in Nottingham, Hull and Stafford, were rented out as offices (often with ‘Burton Buildings’ or ‘Burton Chambers’ over the doorway and in the parapet). Others housed flats for Burton employees.

By 1937 Burton had six categories of building (A to F), the main variable being the number of storeys and the uses to which they were put.

Cambridge (1950)

Lionel Jacobson, Montague Burton’s successor, instituted a programme of refurbishment in 1953, and by 1956 half of the 635 shops had been modernised. It was at this time that high fascias of slatted timber or mosaic tiles were installed, and the inter-war transom lights with their ‘chain of merit’ were concealed or removed. The lettering on the new fascias simply read ‘Burton tailoring’. Fortunately, this was all rather cosmetic, and did not involve wholesale replacement of the pre-war shopfronts.

Leeds, Briggate (c. Historic England Archive)

By and large Burton built far fewer new stores after the war. New stores of the 1950s were much less ostentatious than those designed in the 1930s.

Around 1960, when Burton was doing a roaring trade in Italian men’s suits, some new stores were built in a blocky modern style. Asymmetrical windows were deeply recessed, appearing dark in façades clad in white oblong tiles. Two stores were built on Briggate in Leeds in this style, one including an arcade.

Into the 1970s, shopfronts had pale grey granite stallrisers and pilasters and red Perspex letters illuminated in red neon. Many fascias were sprayed with a textured coating in the 1980s.

Burton’s Architects Department (renamed the Design & Construction Department in 1971) closed in 1975 and it was an external design company that modernised the shops shortly thereafter. Many sites were disposed of by Montague Burton Property Investments Ltd (which had been set up in 1972). There is little to say about Burton’s shops since the 1970s. The maroon-coloured fascia and gold lettering so familiar at the turn of the millennium has more recently given way to very plain squared letters (BURTON), either black on a white ground or vice versa.

Elgin in 2002 (photo: R. Baxter)

Pingback: Burton’s Moderne – Ashton and Beyond

Very much enjoyed reading this article. My Father was a member of the Architects Department at Burtons in Leeds from the late 1950’s until it closed in 1975. Apart from “refreshing” store fronts he was involved in all aspects of the internal refit and also the Burton Retreat, designed and built in York in the late 1960’s. I discovered your piece as I was searching for pictures of “625” the Store I believe was opened on The Headrow in Leeds by Morecombe & Wise in 72.

LikeLike

My father was employed as an electrician on the building of the Hudson Road factory in Leeds. He was then taken on as permanent staff when the factory opened, staying with them for over 40 years. He became deeply involved with the telephone systems, and indeed was a frequent visitor to Sir Montague’s house in Harrogate to attend to their telephones.

He also arranged the sound system for the annual Lorry Driver of the Year competition held in the grounds at Hudson Road.

As a boy he would take me around the factory on a Sunday when he was doing maintenance, during which I was tremendously impressed be the main electricity switch room which to me seemed like a ‘cathedral’ with it’s gleaming polished wooden floor and great black shiny panels holding all the control gear and meters etc. I think this reflected the opulence of the Burton shops.

He met my mother there when working on the roof of the sewing machine roof, he spotted her down through the glass roof.

LikeLike

I worked in the Building Surveyors Dept from 1972 till it was closed 18 years ago. I knew who your father was but did not know him well but worked with 3 people who would have known him Ernest Fairfoot Arthur Conyers and Harry Briggs

LikeLike

Pingback: The Fifty Shilling Tailor and John Collier | Building Our Past

I was employed by Burtons in 1959 as a fifteen years old, at the Morecambe, Lancashire branch, eventually moving to the Church St branch in Liverpool. Every one of my fellow staff members was a ‘Mr’, Nobody used Christian names! It was a great firm to work for and, I have lots of memories of my time with them. I moved to Australia in 1967 and joined a company called Fletcher Jones in Sydney. FJ’s was a similar type of business, but specialising in mens trousers. Now I’m retired and living at Old Bar Beach in NSW. Long time and great distance since May ‘59!!!! Regards to everyone. Stu.

LikeLike

My father worked as a Shopfitter for Burtons in the early fifties, having served his time with Curtiss Shopfitters prior to joining the RNR for the duration of the war. I was employed as Senior Project Manager by Burtons to undertake the refurbished of the 214 Oxford Street building at Oxford Circus. Part of the building was leased to Nike with the remainder refurbished as Top Shop and other Burton brands. Then in 1998 TopShop was the largest fashion store in the World and after refurbishment traded on three basement levels, the only retail outlet to do so at that time in the World, other than in Japan. Pleased to have spent time with a company for whom my father worked for.

Happy times.

Steve.

LikeLike

You mention that the date stones were laid by members of the Burton family and a photo of the one at the Cambridge store. Many of these family members were his children of quite young age (7 or 8 if I recall correctly). No doubt instilling in them the importance of the business and grooming them to take over eventually. As an admirer of Art Deco I enjoy seeing these shops on the High Street and can recall buying a number of suits there.

In the sixties I worked as a programmer for a major bank. One of my projects was to write a program for Burton’s to collect customer payments for their new? store card – clothes on the never-never! It launched in Brighton I think. One of the first systems to use Direct Debit.

LikeLike

The Brighton store is still there, located on the corner of North Street and Western Road. It is now a Waterstones bookshop. The naming stone can be seen at the end of the building on the West Street elevation and, like all the Burton buildings, are easily identified as such,

LikeLike

Pingback: An outside look? | theinfill

During my time in London in the 1980s I worked on the gutting/clearing out of Oxford Street store. (Quite a change from working on the new Lloyds Bank building.)

LikeLike

Hi Paul,

If this was a Burton’s store then likely it was cleared and relocated to allow other Burton brands to occupy it, namely, Dorothy Perkins, Evans etc.

LikeLike

Hi Steve,

Memories of that fine building will never leave me – the different floors and basements etc. The windows and doors facing Oxford Street were all covered with hoarding and entry was gained from the rear.

The display areas inside the windows were very smart and clean long after the fabric of the main building had taken a pounding. A few of us slept in one of the shop windows on a number of occasions – we were comfortable and safe yet only feet from the bustling nightlife outside!

I have some Freddie Laker cologne for men as a souvenir of that adventure.

Paul.

LikeLike

Hi Paul,

A fine building. This started life as a Peter Robinson store. The top floor was where afternoon tea dances were held. Under Burton’s ownership they leased that floor to Air Studios. The Beatles recorded several records there. An apocryphal story was that John Lennon had signed one of the murals, however, studying every mural in detail when scaffold access was available, I never saw any evidence of this. During the refurbishment from 1996 to 1998 my project office was based on the sixth floor in the area that used to house the Burton muniments, as such, the windows were fitted with bars. In the basement there used to be a tunnel that linked the building with the next one in Oxford Street. This was formed in the war in the event that the BBC were required to relocate due to war damage to their building.

In the early nineties the Burton Group was undergoing financial difficulties and sold their interest to Gerald Ronson of Heron about the time he went to prison for the Guinness share scandal. They then leased the store back.

Ah! Freddy Laker and his Skytrain. Memories of scores of people sleeping on Victoria Station concourse. I think you could actually book the flights at Victoria, hence the queues.

Regards,

Steve.

LikeLike

Most interesting Steve.

One of these days I will get to London and walk along Oxford Street with a spring in my step – I feel a lonely sense of happiness thinking thoughts that have not surfaced for very many years.

The 1966 car crash near Redcliffe Square in which the Guinness heir Tara Browne died inspired the writing of the Beatles’ song “A Day in the Life” – Tara’s brother Garech died in London in 2018. (Tara was closer to The Rolling Stones but his death was big news of course.) My late father had a great interest in the stock market and invested in many companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. He was not a drinker and stayed clear of Guinness (and similar) stock but I heard plenty from him about Deadly Earnest Saunders and Co.

Paul.

LikeLike

Hi Paul,

Yes, the amazing Earnest Saunders who was too ill to be tried at the Guinness trial but later staged a remarkable recovery that enabled him to undertake a lucrative public speaking career. ‘‘Twas ever thus.

Best regards,

Steve.

LikeLike

Newton Abbot had a small Burtons – corner of Courtenay and Queen Street – now a mobile phone shop.

I think it’s a similar design to Poole?

LikeLike