‘Drive your car in London. Not so difficult as many women think’, urged Margaret Montague Johnstone in the pages of The Motor in March 1933. As well as being a keen shopper and motorist, Johnstone was the daughter of the first man to go around the world on a bicycle!

Johnstone recommended several choice parking spots around Oxford Street, noting that ‘Debenhams and Freebody have their own private parking ground with an attendant’. You can almost hear the conspiratorial whisper as she adds, ‘how on earth can he tell whether you are really going to shop at Debenham’s or pop down the road to some rival establishment?’

For context, it’s important to realise that in May 1925, when Debenhams opened its innovative Motor Park, kerbside parking in central London was a risky business. Police could cancel an authorised parking space without warning. Furthermore, fines could be issued for locking your car, which had to be removeable at all times. If you didn’t have a chauffeur to guard it, watch out!

Debenhams, which owned both Marshall & Snelgrove in Oxford Street and Debenham & Freebody in Wigmore Street, was the first big store to address customers’ parking anxieties. Its stables and goods yard were flattened to create a free surface car park with 60 spaces marked out in white paint. This operated a ticket system with an electronic indicator board and gong to alert chauffeurs when their cars were wanted.

The idea spread rapidly. In Portsmouth, for example, Knight & Lee began to advertise a free private motor park behind their premises. But it was in London, where the parking problem was most acute, that store car parks proliferated.

Harrods – facing complaints from irate residents in Hans Crescent – bought the nearby Beaufort Garage in March 1926. This provided covered parking for 100 cars. Like Debenhams’ Motor Park, it communicated with the store by telephone so that customers could call ahead for their cars. Three months later Selfridge’s began to offer space in Macy’s multi-storey garage in Balderton Street. The arrangement proved short-lived – Macy’s was sold to The Car Mart – so in 1932 Selfridge’s bought and demolished St Thomas’s church to the rear of the store and proceeded to use the site as a car park.

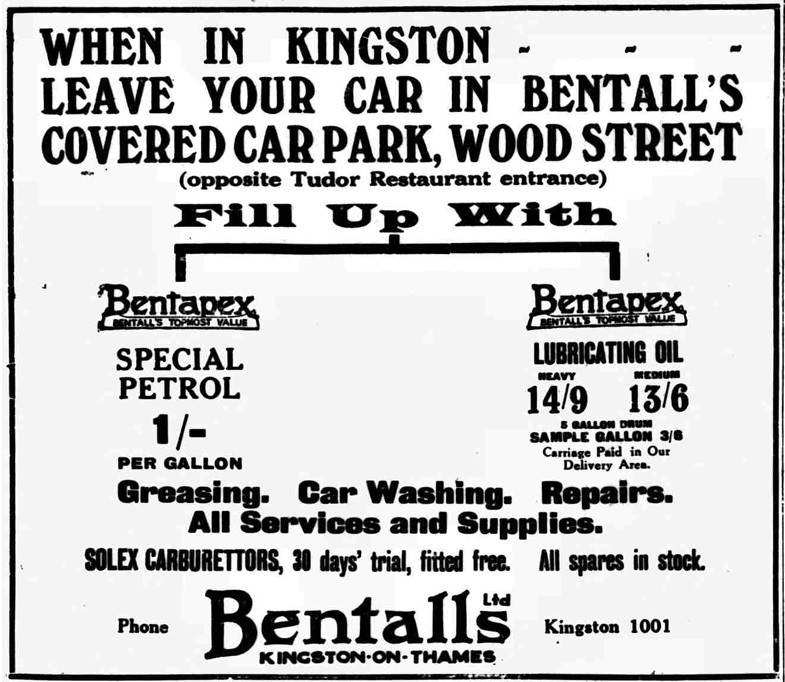

Suburban shopping centres ringing London were becoming congested with traffic by the 1930s. Bentalls in Kingston upon Thames built a huge hangar-like car park shared by delivery vans and customers’ cars. Until now department store car parks had been free, but Bentalls charged 3d. per hour or 6d. for the day. In Croydon, around 1936, Kennard’s opened a free car park with a quick snack counter for owner-drivers and chauffeurs. A year later, the directors of Grants in Croydon were pictured in the press, poring over plans for their customer car park.

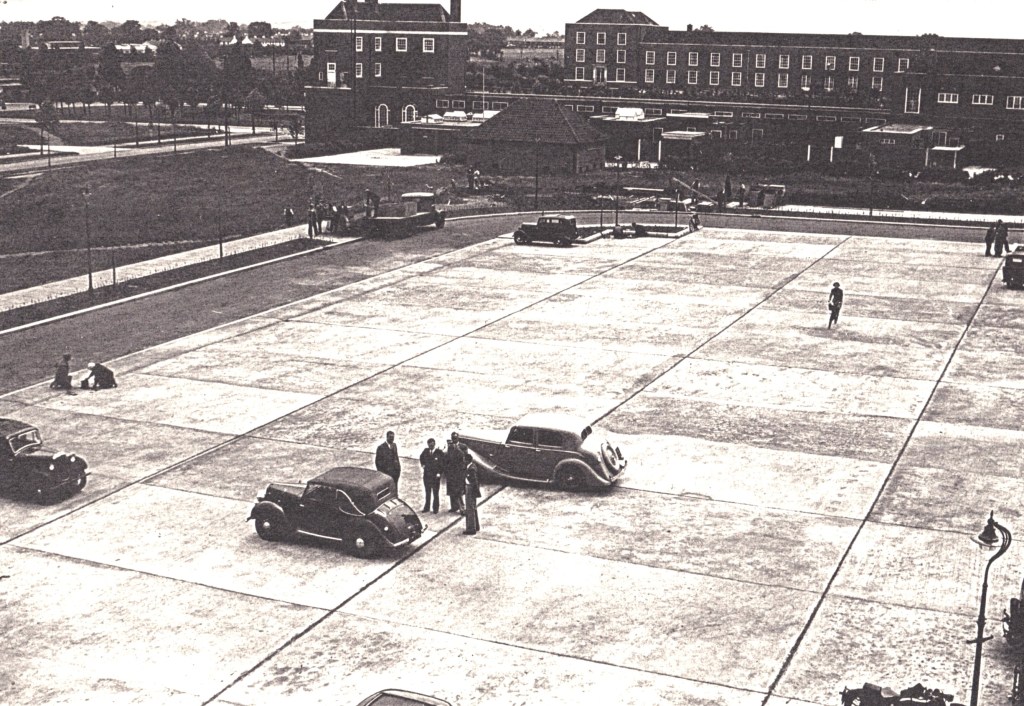

At the very end of the 1930s, Welwyn Stores in Welwyn Garden City built a free surface car park over an underground air raid shelter which was lined with pre-cast concrete units. The concrete slab surface was 12 inches thick. This car park is still used today.

The first multi-storey car park to be built in London after the Second World War was the 800-space Lex Selfridge Garage (1958-60) on Duke Street: a partnership between Selfridge’s and Lex Garages. This may have been influenced by American garage-and-store combinations, such as ZCMI, which had built a car park beside its store in Salt Lake City in 1954. The architects were Sydney Clough, Son & Partners, but the curtain walling was designed by Duke & Simpson. Like pre-war Lex garages, the interior was fitted with long two-way ramps, with attendants on hand to manoeuvre cars using turntables. Drivers were charged 1s. per hour.

By the early 1960s, large car parks were required to serve shopping centres far beyond London and the South East. Increasingly, they were provided by local authorities and the developers of shopping precincts, like the Merrion Centre in Leeds, but many department stores still needed to make private provision. In winter 1960-61 Jenners in Edinburgh employed six ‘girl drivers’ to take customers’ cars to and from the store’s car park, some distance away. This expensive experiment was soon dropped.

New stores usually had to include parking to gain planning permission. The Arnott-Simpson store, built in Glasgow in 1963, got away with just 45 basement spaces. Cole Brothers in Sheffield, also of 1963, was more ambitious, providing a multi-storey car park with a continuous ramped parking floor that could accommodate 400 cars. In keeping with recent developments, the structure had open sides. Exits to the store corresponded to self-operated lifts.

Cole Brothers’ architects – Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall – also designed Keddies’ store in Southend. It occupied the podium beneath an office tower. The initial phase of 1963 included two parking levels served by car lifts (operated laboriously by attendants) and trollies which ran on rails. Phase two, completed in 1972, involved a rooftop car park, allowing the lower parking level to be remodelled as a sales floor.

Keddies was built when enthusiasm for mechanical parking systems was at its height. Before long garages with straightforward staggered ramp systems became standard. In 1968 Debenhams was granted planning permission to rebuild Marshall & Snelgrove’s store in Oxford Street, so long as it provided a multi-storey car park. The resulting building, in Welbeck Street, by Michael R. Blampied & Partners, opened in 1971. Although the parking floors were conventional, the exterior was clad in striking triangular pre-cast concrete units. Upon completion, the garage was handed over to NCP. It was demolished, to howls of dismay, in 2019.

Responsibility for providing parking on such a scale must be recognised as one of the main factors that drove department stores into the arms of the developers who were creating new shopping precincts and malls from the 1960s onwards. Not only was it untenably expensive for stand-alone stores to build their own car parks, but suitable sites became increasingly hard to find. Anchor stores in shopping centres, on the other hand, benefitted from ample shared facilities.

Even today, whenever stand-alone stores are built in central locations – admittedly, a rare occurrence – parking is a critical consideration. One example from 2018 is the John Lewis store in Cheltenham, a redevelopment of a shopping mall which may have been unfeasible without the retained 1991 car park.

Department stores, as a building type, entered a hiatus when the Covid pandemic struck. But so long as we all drive to the shops, their close association with malls or retail parks will remain the norm, with inevitable consequences for our town and city centres.

Text copyright Kathryn A. Morrison (AI scraping not permitted)

Further reading: K. Morrison, English Shops & Shopping, YUP, 2003; K. Morrison & J. Minnis, Carscapes, YUP, 2012

An excellent article. 3d per hour or 6d all day. My residents parking charge in the street outside my house in Brighton is just short of £340 per annum and likely to rise again next year. Changing times.

Steve Hodgson.

LikeLike