Introduction

The impending closure of Beales in Poole – the last store to bear that well-known name – offers an opportunity to reflect upon the history of this important British department store group. Throughout its existence it opened (and closed) around 45 shops and stores.

The founder, John Elmes Beale (1848-1928), profited from the enormous commercial growth of Bournemouth in the Victorian era. He presided over one of the town’s main stores and served three terms as mayor.

At the time of his death, Beale’s company – managed by his sons – operated two department stores in Bournemouth and one in Eastbourne. Let’s start by looking at these in turn.

Beales, Old Christchurch Road, Bournemouth

The story begins in 1881. After working for many years with a draper in his home town of Weymouth, Beale opened the Fancy Fair at 3 St Peter’s Terrace, Bournemouth. Concentrating on fancy goods and toys, this was one of the first British stores to engage a live Father Christmas.

Business boomed, and by 1889 the store had spread into the corner of Old Christchurch Road, next door to the original shop. This extension was named Oriental House. It may have been inspired by the oriental bazaar of Liberty’s, whose art fabrics Beale stocked (as sole Bournemouth agent).

Oriental House was rebuilt in 1911 to designs by J. F. Watkins, who beat 37 other architects to win the contract. Upper floor showrooms were lit by expansive windows and topped by large signs and a clock turret. This proclaimed the store from afar.

In 1931, the entire store was rebuilt to designs by North, Robin & Wilsdon, prolific retail architects who had recently completed Beale’s Eastbourne branch (see below). They worked alongside Hawker, Mountain & Bailey. The new building boasted 40 departments, seven lifts and two escalators. The Mexican Cafe opened in 1936, with waitresses dressed in appropriate costumes and live music played by Beales Blue Orpheans.

In May 1943 the 12-year-old store was destroyed by bombing. The design of its monumental seven-storey replacement, drawn up in 1950, was informed by travels undertaken by the family and their architects, Jackson & Greenen, not just in this country, but ‘in the Dominions and elsewhere’. The moderne character of the building, with its hints of Mendelsohn’s Schoken, suggests that they were particularly inspired by 1930s precedents. The store closed in 2020.

Bealesons, Commercial Road and The Avenue, Bournemouth

In 1920, J. E. Beale Ltd. took over the drapery of William H. Okey – a close friend and business partner – at 7-13 Commercial Road and 7-13 Avenue Road. Okey’s store, managed by Harold Beale, was renamed Bealesons around 1925.

A modern extension was added on Commercial Road in 1934. This was designed by Reynolds & Tomlis, with shopfitting by D. Drake & Son. The building served primarily as a men’s store, with an arcade devoted to the display of men’s clothing. A new staircase led up to a furniture department. Beales was still adept at publicity, and the principal draw at the opening was a ‘mechanical mannequin’ named M. de Patou.

The combination of a man’s shop and a furniture department may have been inspired by Barker’s in Kensington, which had erected an extension for these departments in the 1920s.

Bealesons unified its old-fashioned façades with louvred cladding in 1962. This was replaced after Bealesons closed in 1982 and the site was redeveloped as The Avenue. Around 2019 the 1980s cladding was removed and the old frontages restored.

Beales, Eastbourne

In 1927 Beales built a new store on the corner of Trinity Trees and Terminus Road in Eastbourne. The architects, North, Robin & Wilsdon, worked with many of the same contractors for C&A around the same time.

The store still stands, but the bays between the faience pilasters have been reclad in a humdrum manner. This was probably the work of the Brighton Co-operative Society, which bought the store in 1946, following a period of wartime closure and requisition.

The Creation of the Beales Group

A branch of Beales (later renamed Bealesons) opened in the Arndale Centre (later Dolphin Centre), Poole, in 1969. Similarly, a Beales store opened in a mall development, The Brooks, in Winchester in 1991. Otherwise, the group expanded by acquiring going concerns, rather than by entering new shopping centres.

At this time department store groups like Debenhams and House of Fraser were evolving into chains, chiefly by installing computers and enforcing central buying. Beales attempted to retain the individual profile of its associated stores for as long as possible, whilst focusing on ABC1s aged over 35.

Floyds in Minehead, bought in 1978, became a short-lived branch of Bealesons. Later purchases included the following: Grant Warden in Walton-on-Thames (1979); E. Braggins & Sons in Bedford (1982); Broadbents & Boothroyds in Southport (1993); Whitakers in Bolton (1996); Denners in Yeovil (1999), and J. R. Taylor in Kendal (1999). Most of these stores (if they survived long enough) kept their own names until 2011. They also retained much of their original shopfitting.

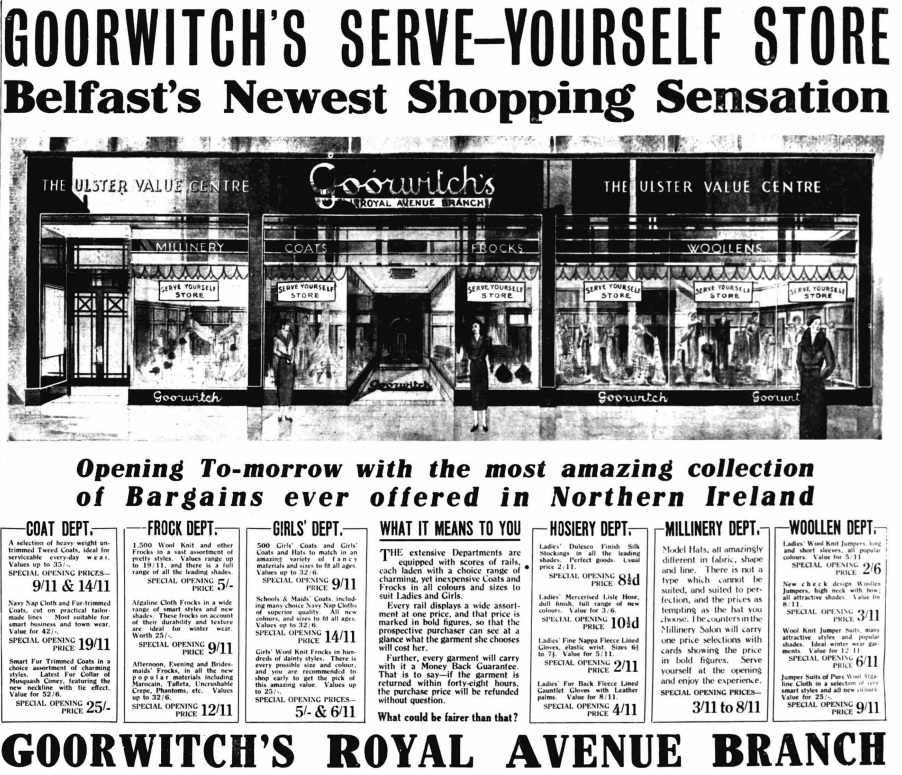

Other stores joined the stable in the early 21st century, including Bentalls stores in Ealing, Tonbridge and Worthing, bought from Fenwicks in 2002. Others were Allders in Horsham (2006) and Robbs in Hexham (2010). This growth was assisted by the flotation of the company – previously one of the largest independent department store groups in the country – in 1995. Initially, the Beale family retained most of the company’s equity, but ceded its management to others.

The Beale Group experienced a spurt of growth in 2011, when it acquired 19 Westgate department stores from the Anglia Regional Co-operative Society. This included stores in Beccles, Bishop Auckland, Lowestoft, Peterborough and Wisbech.

Final Struggles

The group subsequently struggled, closing 10 loss-making stores in 2016 and submitting to a management buyout in 2018. This returned the company to private ownership. The most recent of its 21 outlets at this time were two Palmers stores, in Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft, and McEwens of Perth, all bought in 2017. McEwens was the only Scottish store owned by Beales.

Beales still operated 23 stores when it entered administration, on the eve of the COVID pandemic in January 2020 (just three months before Debenhams also hit the buffers). New Start 2020 Ltd. (Panther Securities) rescued the Poole, Peterborough and Southport stores. Peterborough and Southport closed in 2023 and 2024 respectively. The closure of the Poole store on 31 May 2025 marked the end of the Beales and Bealesons story.

Text copyright Kathryn A. Morrison (AI scraping not permitted)

READ MORE about historic department store groups and chains in Kathryn A Morrison, Chain Stores in the Golden Age of the British High Street, Liverpool University Press, 2025.