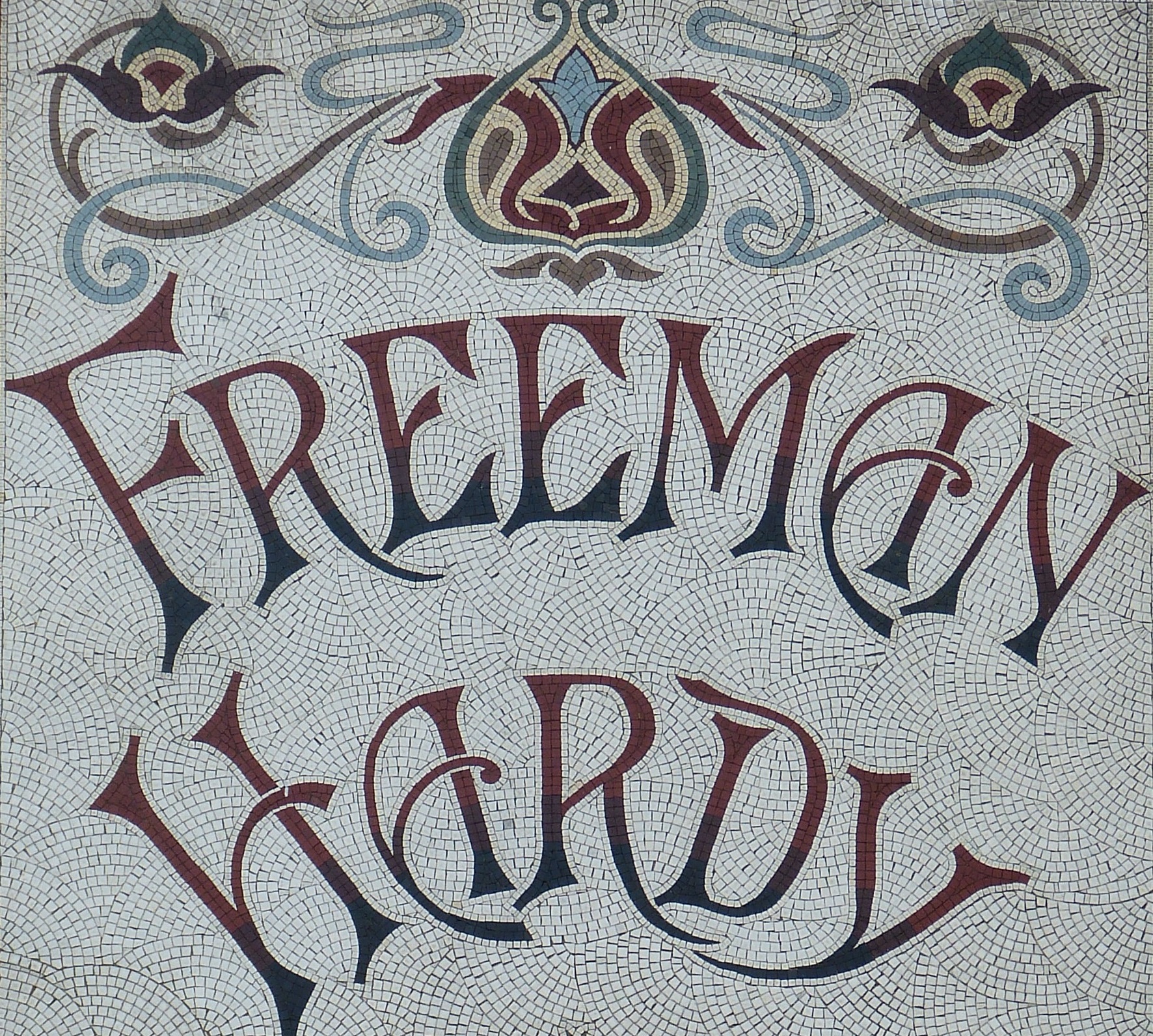

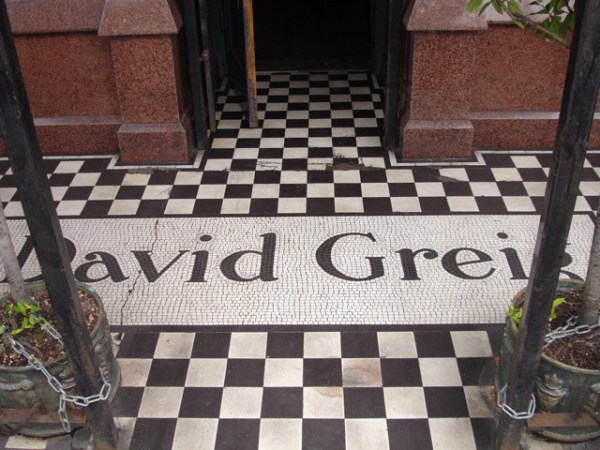

Market Place, Hitchin: detail of mosaic sign. (R. Baxter)

Introduction

Boot and shoe dealers were amongst the first chains of shops to emerge in the mid-to-late 19th century. Many sprang up when footwear manufacturers decided to eliminate the middleman and sell their products direct to customers through their own retail branches. A few, like Timpson, subverted this commercial model by starting as retailers and only later branching into manufacture.

Early chains included Freeman, Hardy & Willis, Cash & Co, Lilley & Skinner, Stead & Simpson, True-Form, Lennard and Milwards. Following in their footsteps in the 20th century were Barratt, Manfield, Saxone, Lotus & Delta, Dolcis, Peter Lord (Clarks), and many more. Once household names, most of these have long gone. They thrived in an age before imports effectively destroyed Britain’s native footwear industry, severing the link between the factories and their outlets.

This series of posts on the shoe shops of the past begins with Freeman Hardy & Willis, whose fascia was a common sight on British high streets until the company’s demise in 1996.

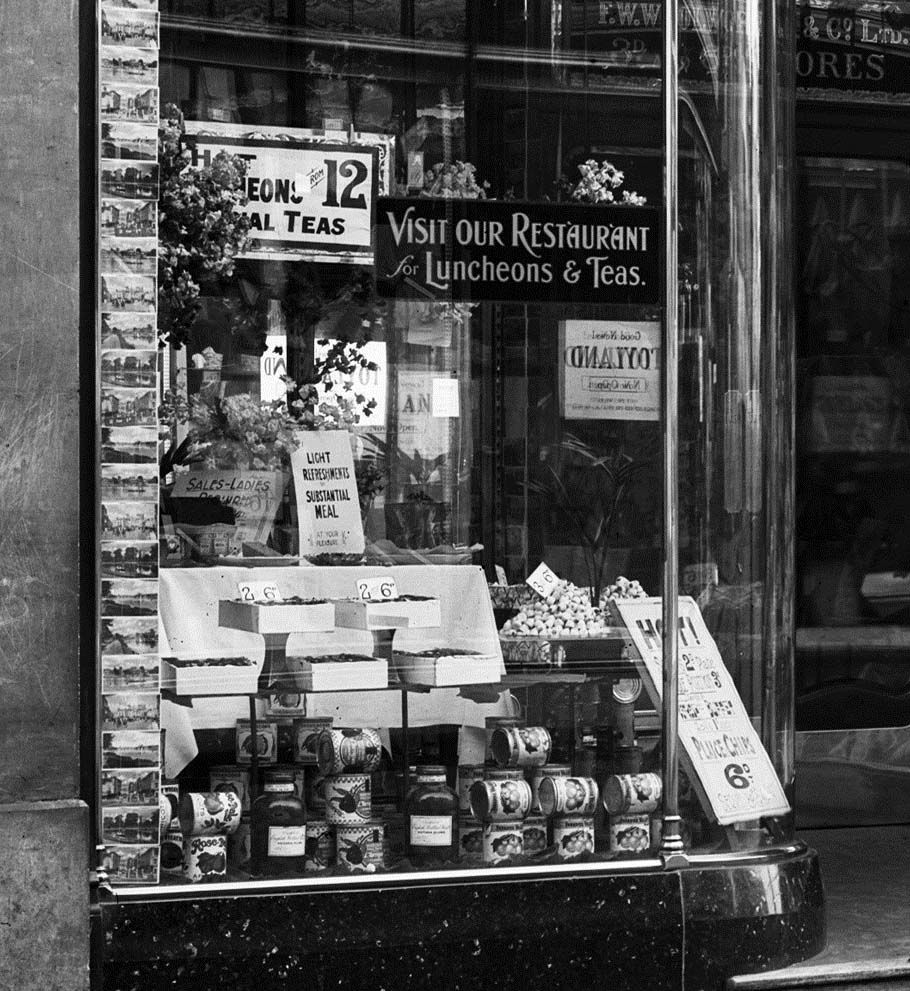

Sandwich, photographed 2009

The Story of Freeman, Hardy & Willis

Freeman, Hardy & Willis was created in Leicester in 1875 and formed into a limited liability company with £20,000 capital in December 1876. Described as ‘boot and shoe manufacturers and factors and leather merchants’, it was named after its three directors: William Freeman, Arthur Hardy and Frederick Willis. Rather remarkably, Hardy was an architect by profession. Soon after incorporation, in 1877, the partnership was dissolved and the company merged with E. Wood & Co., a manufacturing firm established by Edward Wood (1839-1917) in the 1860s. As Chairman, Wood assumed responsibility for the subsequent success of Freeman, Hardy & Willis. He became a local worthy, receiving a knighthood in 1906 and serving as mayor of Leicester on four occasions.

Pearl granite stall risers and mosaic floor at Bideford, c.2000. (K. Morrison)

Shops bearing the Freeman, Hardy & Willis signboard began to open by 1879, if not before. Early branches included Leamington Spa, Lincoln and Leeds. These outlets retailed own-brand footwear for men, women and children and, like most multiples, sold for ‘ready money’ (cash) only. They were stocked from a ‘handsome warehouse and manufactory’ built in Leicester in 1876-77. Occupying the corner of Rutland Street and Humberstone Road, the building was constructed by Gilbert & Pipes, local builders, at a cost of £6,100. It was fitted with up-to-date machinery, including Wright’s blocking machines, Gimson’s presses and Grimes’ lift cutters. The manager was John Butcher. No evidence has turned up, but one wonders if Arthur Hardy was the architect.

Freeman, Hardy & Willis’s works on Rutland Street, Leicester, in 1878

Growth was astonishingly rapid. By 1887 Freeman, Hardy & Willis boasted 130 outlets. This grew to 150 by 1890, 200 by 1894, and 300 by 1903, when the London chain Rabbits & Sons was acquired. Later takeovers included Pocock Bros. and Hall & Co. These acquisitions helped Freeman, Hardy & Willis expand to 460 shops on the eve of war in 1914. In the early years the firm was advertised as ‘The Boot Kings’, ‘The Boot People’ or ‘The People’s Boot Providers’, but by 1900 it was claiming to be ‘The Largest Boot and Shoe Dealers in the World’. By then the shops had separate ladies’ rooms and repair departments.

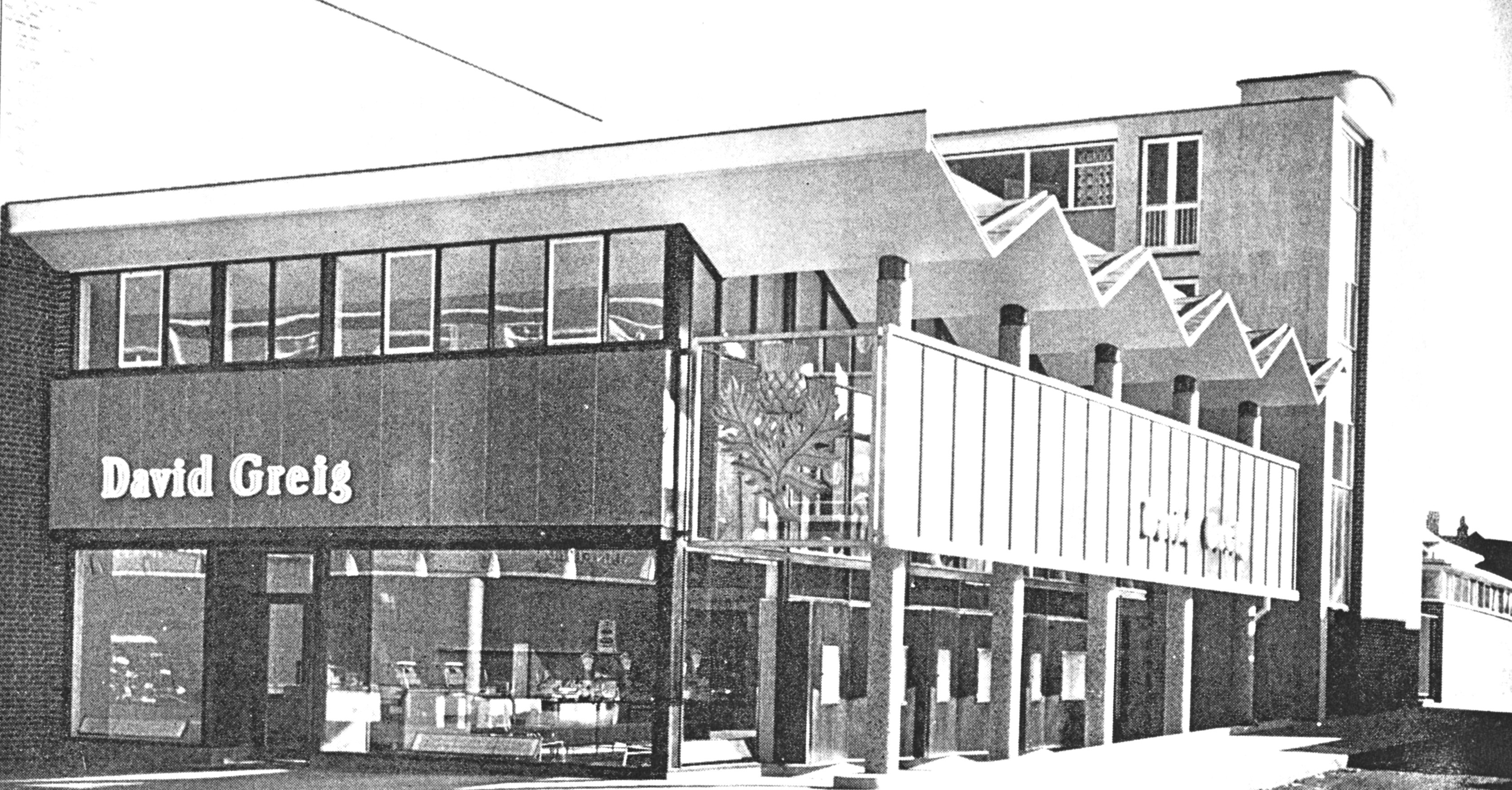

Repair Depot, Orchard Street, Canterbury. This building probably dates from c.1925-30. Behind the façade the workshop was lit by north-facing lights in a sawtooth roof. (c.Historic England)

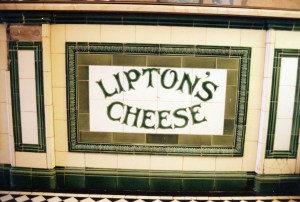

Information about Freeman, Hardy & Willis’s building and shopfitting activities is not easy to come by, though disparate archives exist and this might be a fruitful field of study (for someone else, some day!). Evidently some properties were bought outright whilst others were leased, and the majority were converted or refitted rather than being new-build. The most tangible remnants of the shops are mosaic tiles on the floors of entrance lobbies, with the initials ‘FHW’ rendered in various styles. In addition, a very splendid mosaic sign survives on the canted corner of a building that housed the Hitchin branch from c.1900. The shopfitter F. E. and G. Maund was responsible for the branch in Forest Gate in 1898, and may have worked for the firm on a regular basis.

Market Place, Hitchin, Hertfordshire. (R. Baxter)

Hitchin. (K. Morrison)

In 1908 Freeman Hardy & Willis announced that it was discontinuing manufacture in London – presumably a reference to a factory inherited from Rabbits & Sons – to concentrate on its Northamptonshire factory, which was in the throes of extension. The Kettering Boot & Shoe Co., which had supplied Freeman Hardy & Willis since 1879, was taken over directly in 1913 (factory dem. 1996). Jonathan North (1855-1939) was appointed Sir Edward Wood’s successor as the Chairman of Freeman Hardy & Willis in 1912 and subsequently, in 1925, Leavesley & North Ltd was acquired. In 1928 Freeman, Hardy & Willis was bought out by J. Sears & Co, which traded as the True-Form Boot Co of Northampton. Once united, True-Form and Freeman, Hardy & Willis – which maintained their separate identities – had 720 shops.

In 1908 Freeman Hardy & Willis announced that it was discontinuing manufacture in London – presumably a reference to a factory inherited from Rabbits & Sons – to concentrate on its Northamptonshire factory, which was in the throes of extension. The Kettering Boot & Shoe Co., which had supplied Freeman Hardy & Willis since 1879, was taken over directly in 1913 (factory dem. 1996). Jonathan North (1855-1939) was appointed Sir Edward Wood’s successor as the Chairman of Freeman Hardy & Willis in 1912 and subsequently, in 1925, Leavesley & North Ltd was acquired. In 1928 Freeman, Hardy & Willis was bought out by J. Sears & Co, which traded as the True-Form Boot Co of Northampton. Once united, True-Form and Freeman, Hardy & Willis – which maintained their separate identities – had 720 shops.

Letchworth, 1930s: note the date 1877 in the window.

Freeman, Hardy & Willis’s Rutland Street headquarters was bombed in 1940. Following a close study of American warehouse methods, a new modern office block – Enterprise House – was erected on the old site in 1955-57, to designs by Lewis Solomon Son & Joseph. This was converted into a hotel around 1970, but the site is currently being redeveloped yet again.

The Rutland Street Headquarters in 2001. (c.Historic England)

Catford.

One particular Freeman, Hardy & Willis shop caught the imagination of the architectural press after the Second World War. This was the Catford branch, built in 1953 to a design by the modernist architect Patrick Gwynne (1913-2003). Set on a corner, the recessed shopfront featured display cases wrapped around structural columns, suspended signs, and staggered display shelving. The shopfitting was by A. Davies & Co of London, who were also responsible for the Putney branch of the late 1950s. The architects of Putney were Bronek Katz & Vaughan, who also worked for Bata. Bronek Katz & Vaughan had probably been commissioned by Nadine Beddington, who became Freeman, Hardy & Willis’s advisory architect in 1955. From 1957 until 1967 she was the Chief Architect to Freeman Hardy & Willis, True Form and Character Shoes, all part of the British Shoe Corporation (BSC).

The BSC was the brainchild of Charles Clore. As Chairman of J. Sears & Co, he sold a great deal of shop property in 1953, raising millions which he invested in diverse businesses. The umbrella company was renamed Sears Holdings in 1954. It acquired Character Shoes, a 50-strong chain, in 1954, then Curtess Shoes, Manfield, with 180 branches, and Dolcis, with 250 branches, in 1956. These were bundled together as the BSC, with six factories and 1,500 shops. Saxone and Lilley & Skinner, which had merged in 1956, were acquired by the BSC in 1962.

The former Leominster branch in 2000. Note the lobby floor as well as the ghost lettering on the fascia. (K. Morrison)

By the early 1990s times had changed. A struggling BSC was restructuring and Sears was selling off hundreds of poorly-performing shoe shops. Changing footwear fashions and cheap foreign imports had transformed this area of retailing. Freeman Hardy & Willis was sold to Fascia for £11.7 million in 1995. Fascia’s collapse a year later brought about the closure of all remaining Freeman, Hardy & Willis shops. Just scant traces of the firm survive, notably its mosaic tiling, but not enough to leave a strong impression of a distinctive and lasting house style.

Click here to read about the boot and shoe industry in Northamptonshire.

![DSCN0043[1] crop](https://buildingourpast.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/dscn00431-crop.jpg?w=284)

![DSCN0030[1]crop](https://buildingourpast.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/dscn00301crop.jpg?w=358)

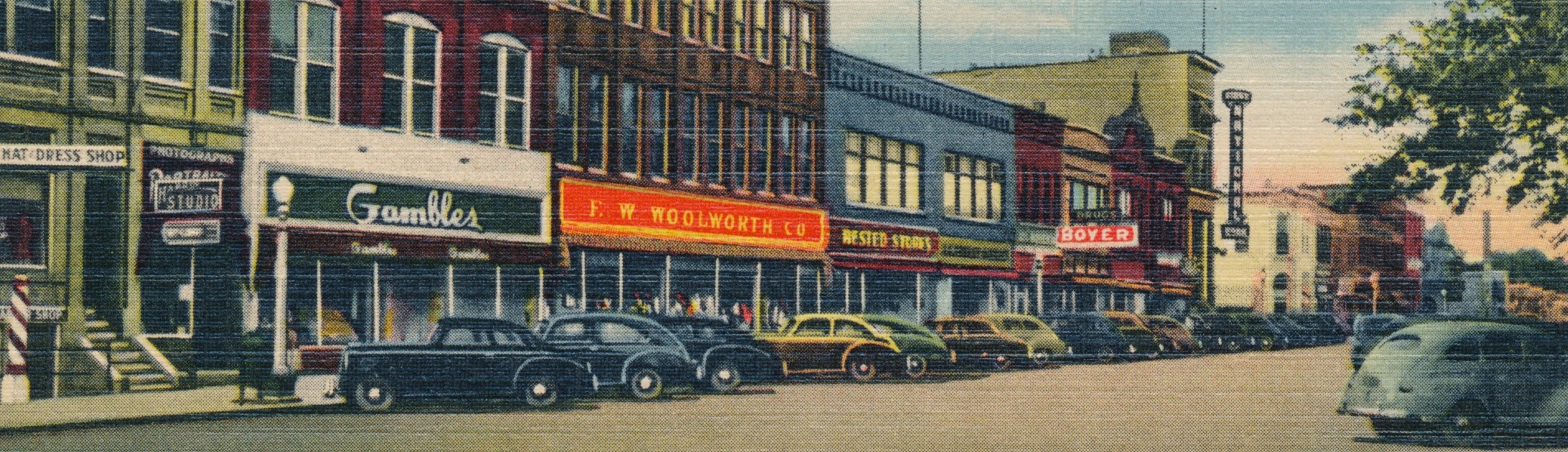

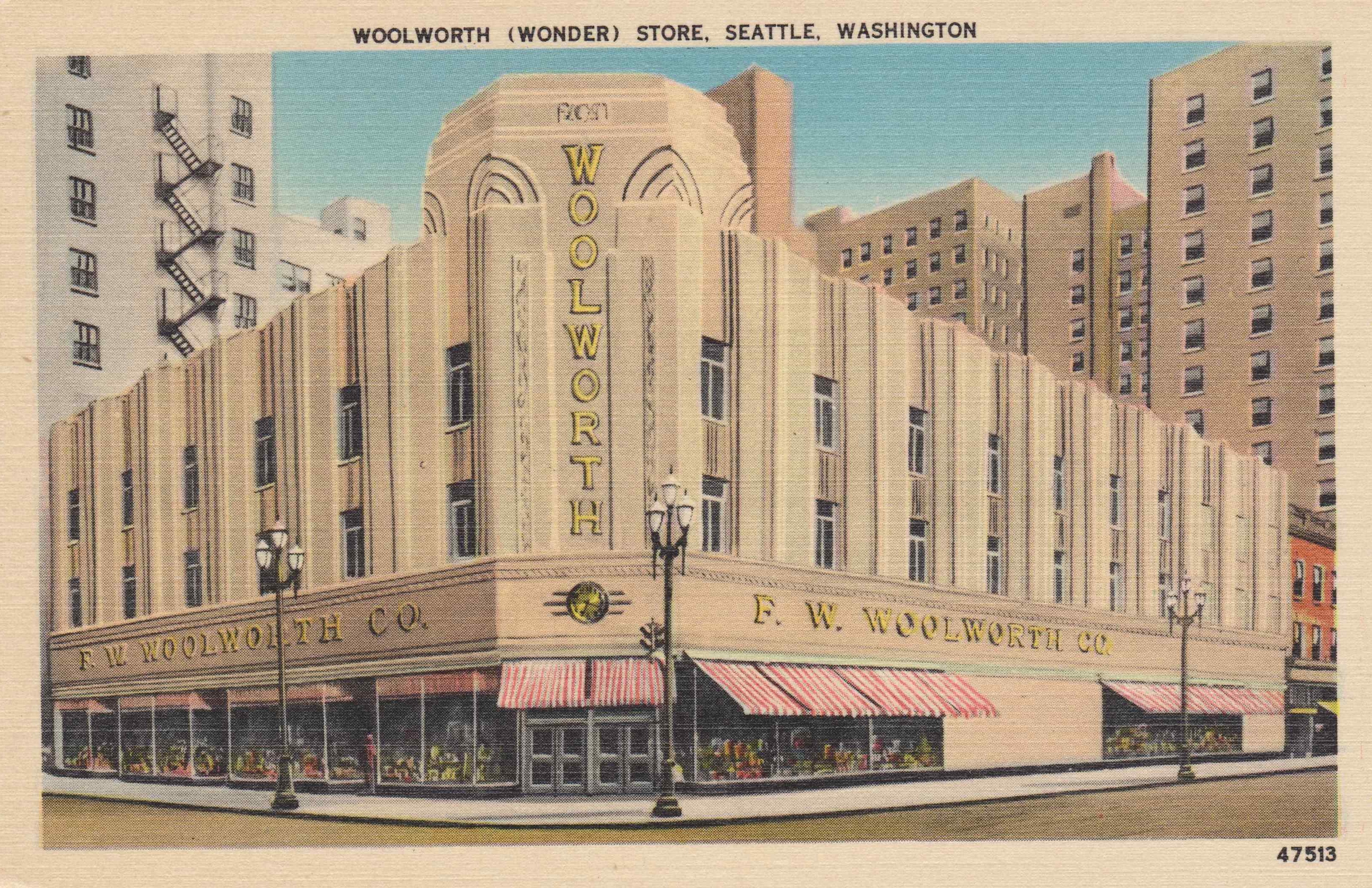

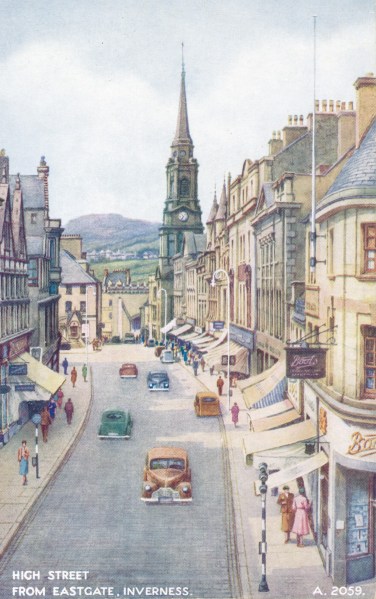

The appeal of Inverness to the typical visitor was certainly not its modernity, rather its charm as a traditional Highland town. Here it is depicted by another Valentine’s artist, B.F.C. Parr. Again the series number implies a date of 1935. As yet, art deco store fronts like Burton’s in Newcastle had not disrupted the gentility of the High Street, and the prevalence of retractable awnings was distinctly old fashioned. Nevertheless, it is notable that the cars are up-to-date and a new-fangled traffic light is prominent in the foreground. Perhaps the town fathers thought that such amenities would attract the touring motorist. The only multiple retailer with an obvious presence here is Boots, a company much less aggressively modern in its approach to buildings than Woolworth or Burton.

The appeal of Inverness to the typical visitor was certainly not its modernity, rather its charm as a traditional Highland town. Here it is depicted by another Valentine’s artist, B.F.C. Parr. Again the series number implies a date of 1935. As yet, art deco store fronts like Burton’s in Newcastle had not disrupted the gentility of the High Street, and the prevalence of retractable awnings was distinctly old fashioned. Nevertheless, it is notable that the cars are up-to-date and a new-fangled traffic light is prominent in the foreground. Perhaps the town fathers thought that such amenities would attract the touring motorist. The only multiple retailer with an obvious presence here is Boots, a company much less aggressively modern in its approach to buildings than Woolworth or Burton.