The interior of Wolseley’s Niagara Garage in 1913 (c. Historic England, Bedford Lemere)

One of the most unusual garages in early 20th-century London was the Niagara Garage on York Street (now Petty France) in Westminster. This had been built as a panorama, and later used as an ice-skating rink.

The building, described rather optimistically as a ‘portable’ iron structure, was designed by the wonderfully-named architect, Robert Emeriti Tyler (1840-1908). Behind a neo-classical façade it included two halls, one circular and the other rectangular, each surrounded by galleries. It opened in 1881 as the Westminster Panorama with the Battle of Waterloo but was reinvented in 1883 as the National Panorama, showing the Battle of el Kebir. In 1888 it became the Niagara Cyclorama and Museum, exhibiting a cycloramic painting by Paul Philippoteaux called ‘Niagara in London’. This was enormously popular, and the building came to be known as Niagara Halls, or simply Niagara.

An American theme pervaded the Niagara:

Besides the attractions of the Falls and the Rapids visitors will find a real Indian store, such as you may see in Niagara village. Here you will be able to buy Indian beadwork, mocassins, canoes, and all manner of curios. There will be no doubt to their genuineness, for half a dozen real Indians will be at work within. A troop of negro waiters have also been imported from Buffalo, to minister to the bodily requirements of the visitor (Pall Mall Gazette, 27 February 1888, 5).

The ticket hall of Niagara in 1888 (c. Historic England, Bedford Lemere)

In 1893 the Niagara panorama was transformed from summer to winter by the judicious application of white paint, and in 1895 the circular central space was converted into an ice-skating rink with plant by L. Sterne & Co. The Niagara panorama was retained as a backdrop, and the gallery became a lounge.

Fig: Skating at Niagara, with the famous panorama in the background (ILN 19 January 1895)

The skaters’ paradise closed in spring 1902, and the Niagara canvas (400ft by 38ft) was sold off for £200. The property was bought by an electric car company, the City & Suburban Electric Carriage Co., which already (indeed, since shortly after its formation in 1901) occupied a garage with an electric lift in Shaftesbury Buildings, 6 Denman Street, Piccadilly.

The use of the Niagara as a garage had American precedents. In 1897 ‘the first recorded parking garage in the United States’ had come into existence when a skating rink at 1684 Broadway, New York, was taken over by the Electric Vehicle Co., and amongst the first parking structures in Boston and Washington DC were converted cycloramas.

City & Suburban could store around 230 vehicles at Niagara, compared with 100 at Denman Street. This was undoubtedly one of the largest garages in London. While City & Suburban offered some vehicles for hire, its main business was car sales – patrons included the King, Queen and Prince of Wales – and all-inclusive garaging and servicing. Year-round garaging was a novelty in 1902:

The rapid disappearance, in the residential parts of town, of space available for accommodating our motors suggests their being housed together. So for a tariff of £12 or £14 monthly, the company undertakes to house, clean, lubricate, and generally supervise your car, supply it with current, and insure it against damage and injury. On a rather higher tariff, the batteries, tyres, and all working parts will be renewed, and you may therefore command an exclusive and handsome vehicle by day or night, with neither horse to die, nor stable to maintain (Pall Mall Gazette, 26 December 1902, 7)

After City & Suburban was wound up in winter 1903-04, the Niagara Garage appears to have been kept up by the liquidator. Throughout 1904-05 part of the premises was let as offices to a hire company, the Electric Landaulette Co., which retained its main garage in Chelsea. In 1905 the liquidator sold the business, including the Niagara and Denman Street garages, to the Wolseley Tool & Motor Car Co., a Birmingham motor-car manufacturer. Wolseley concentrated City & Suburban’s business at Niagara, opening there in 1906.

Inside the Niagara in 1913: note the car lift (c. Historic England, Bedford Lemere)

Wolseley’s head staff were transferred to London from Birmingham. Niagara became the London Sales Depot and Garage, managed by J. E. Hutton. In 1921 Wolseley opened splendid new showrooms on Piccadilly, now the Wolseley restaurant.

Wolseley could garage 60 cars in the central space – the former panorama and ice rink – with another 50 on the gallery, plus 22 in lock-ups. The gallery was served by an electric car lift and heated by hot-water pipes. Its upper walls (where the panorama had originally hung) were plastered with advertisements – interesting, considering that the first advertising exhibition in London had been held in Niagara Hall in 1899. The complex included a glass-roofed washing space, a small repair shop which could be used by chauffeurs, a reading and recreation room with lavatories and cloakroom, and a main repair shop with trestles for cars, rather than pits. Smoking was prohibited!

Inside Niagara in 1913, showing lock-ups on the gallery (c. Historic England, Bedford Lemere)

Wolseley was continuously improving its facilities at Niagara: around 1910 an underground level was created and an extra lift was installed; in 1911 it became the official RAC garage; also in 1911, it opened a Motoring School, and introduced gates by the timekeepers’ lodge which could be raised and lowered, controlling entry and exit.

The Niagara’s new underground parking level in 1913 (c. Historic England, Bedford Lemere)

The Timekeeper’s Lodge and barriers in 1911 (RAC Journal, 8 September 1911, 186)

In 1927 the Niagara was taken over by the Westminster Garage Ltd. It was remodelled by E. H. Major in 1928 to provide chauffeurs with first-floor bedrooms, mess rooms and recreation rooms; its kitchen served meals from 8am until midnight. The building survived the Second World War and was probably demolished around 1970.

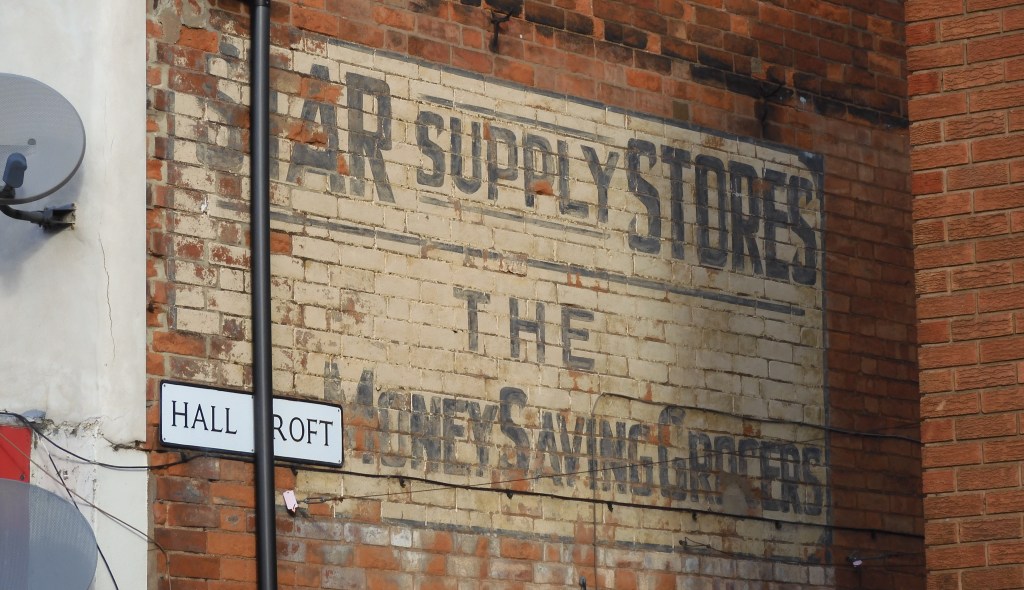

Stumbling across the wonderful Star Supply Stores on Lowestoft’s historical High Street – now Raphael Crafts – prompted a bit of research into this retail business. Star was one of many chains of grocers and provision dealers that thrived in English towns during the late 19th and early-to-mid 20th centuries.

Stumbling across the wonderful Star Supply Stores on Lowestoft’s historical High Street – now Raphael Crafts – prompted a bit of research into this retail business. Star was one of many chains of grocers and provision dealers that thrived in English towns during the late 19th and early-to-mid 20th centuries. In the late 1870s Cadman moved his family and business to Derby. By the time Fish retired in 1888, and the partnership was dissolved, they had amassed an impressive portfolio of retail businesses (listed in the Western Daily Press, 4 January 1888, 8). Most of their shops – of which there were over 40 throughout England – traded as ‘The Star Tea Company’. Other were:

In the late 1870s Cadman moved his family and business to Derby. By the time Fish retired in 1888, and the partnership was dissolved, they had amassed an impressive portfolio of retail businesses (listed in the Western Daily Press, 4 January 1888, 8). Most of their shops – of which there were over 40 throughout England – traded as ‘The Star Tea Company’. Other were: The first shop to adopt the name ‘Star Supply Stores’ appears to have been the branch at 5 Queen Street, Oxford, in 1887. After Star became a limited liability company in 1892, however, this name supplanted that of the Star Tea Company on fascias across the chain.

The first shop to adopt the name ‘Star Supply Stores’ appears to have been the branch at 5 Queen Street, Oxford, in 1887. After Star became a limited liability company in 1892, however, this name supplanted that of the Star Tea Company on fascias across the chain. In 1890 Cadman retired to Brighton, leaving the business in Spofforth’s hands. He sold his home, shop and stores in Derby. This considerable property included a house called ‘The Cedars’ in Breadsall, a shop at 182 Normanton Road, together with commercial premises bounded by Haarlem Street, Waterloo Street and Britannia Street in Derby with ‘ . . . the extensive Mill Premises, Warehouses, Stores, Engine Sheds, Yards, Dwelling-house and appurtenances . . .’ (Derbyshire Advertiser & Journal, 12 December 1890, 1). Today this site is covered by a major traffic interchange – even the street names have been eliminated. Cadman enjoyed a short retirement in Brighton before dying in 1897. He left a colossal fortune of £95,000.

In 1890 Cadman retired to Brighton, leaving the business in Spofforth’s hands. He sold his home, shop and stores in Derby. This considerable property included a house called ‘The Cedars’ in Breadsall, a shop at 182 Normanton Road, together with commercial premises bounded by Haarlem Street, Waterloo Street and Britannia Street in Derby with ‘ . . . the extensive Mill Premises, Warehouses, Stores, Engine Sheds, Yards, Dwelling-house and appurtenances . . .’ (Derbyshire Advertiser & Journal, 12 December 1890, 1). Today this site is covered by a major traffic interchange – even the street names have been eliminated. Cadman enjoyed a short retirement in Brighton before dying in 1897. He left a colossal fortune of £95,000. In 1922 the Star Tea Company, with 321 shops, acquired control of Ridgways Ltd., a London-based tea importer and dealer founded in 1836. The two companies had been closely associated for some time. In 1928-29, however, the Star Tea Company (with Ridgways) was taken over by the

In 1922 the Star Tea Company, with 321 shops, acquired control of Ridgways Ltd., a London-based tea importer and dealer founded in 1836. The two companies had been closely associated for some time. In 1928-29, however, the Star Tea Company (with Ridgways) was taken over by the  Very few Star Supply Stores shopfronts are known to survive – Lowestoft is rare – and those recorded in old photographs suggest that there was no hard-and-fast house style. However, the company regularly installed brass stall plates engraved with the Star name. Some transom lights held glass etched with a star (something to look out for!) and occasionally a star-shaped hanging sign projected from the frontage. The name was repeated on an opaque lamp shade over the entrance lobbies – the hook for this can still be seen at Lowestoft.

Very few Star Supply Stores shopfronts are known to survive – Lowestoft is rare – and those recorded in old photographs suggest that there was no hard-and-fast house style. However, the company regularly installed brass stall plates engraved with the Star name. Some transom lights held glass etched with a star (something to look out for!) and occasionally a star-shaped hanging sign projected from the frontage. The name was repeated on an opaque lamp shade over the entrance lobbies – the hook for this can still be seen at Lowestoft.