Bristol in 1999

The last of BHS’s war-damaged stores to be rebuilt was Bristol, where a ‘temporary’ store had traded for many years. The new building opened in 1960 on a corner site and had an attractive concave frontage with a sweeping canopy to shelter window shoppers. The contemporary store in Scunthorpe – on the site of the Trinity Methodist Church bought for BHS by S. H. Chippendale (surely none other than Sam Chippendale of Arndale) in 1959 – had a blind concave corner bay, on which the name of the company was prominently displayed. Also in 1960, the Peckham and Bedminster stores closed and were rapidly rebuilt.

Peckham in 2009

Gloucester (Beecroft, Bidmead & Partners, 1965) in 1999

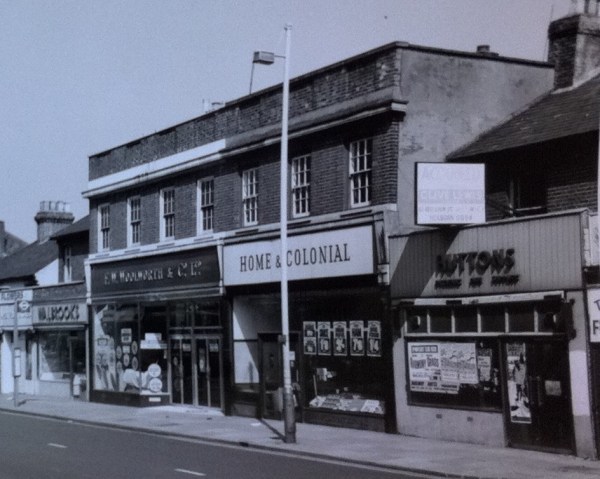

Rather astonishingly, BHS had no presence on London’s Oxford Street until 1961, when it took a major unit, with 33,000 sq. ft. sales space, on the ‘East Island Site’ – next to John Lewis and beneath the London College of Fashion. Other new or comprehensively rebuilt stores of the early 1960s included (first list alert!): Bradford (1961; cafeteria, 1962), Rotherham (1962), Sutton (1962), Woolwich (1962), Watford (1963, with an extension of 1966), Wembley (1963), Sheffield Moor (1963), Kirkcaldy (the first Scottish branch, 1964), Swindon (1964), Tooting (1964), Gloucester (1965), Belfast (the first branch in Northern Ireland, 1965), Chester (1965), Sheffield Haymarket (1966), Ilford (1966), Bolton (1966) and Doncaster (1966).

Tunbridge Wells in 1999

At the same time, many older branches were extended, including (second list alert!): Slough (1960), Bedford (1960), Kilburn (1960), Nottingham (1961), Tunbridge Wells (1961), Gravesend (1961-2), Hounslow (‘modernised’ 1961), Taunton (1961-2), Sunderland (1961-2), Croydon (1961-3), Chatham (1963), East Ham (1963), Dudley (1966), Luton (1966), Portsmouth (1966), Lowestoft (1966) and Putney (1966). Harlesden had to be rebuilt after a fire in 1961. BHS closed small branches that could not be extended, such as Edgware Road (1960), Upton Park (1961), Salford (1967) and Stratford (1967). It also shut stores deemed to have limited trading potential, like Ilkeston and Dagenham (both 1965).

In 1961 Sir Richard Burbridge (1897-1966), recently ousted from Harrods by Hugh Fraser, became Chairman of BHS. Around this time the brand name ‘Prova’ was applied to the full range of merchandise, with the exception of toiletries and cosmetics. The company considered its main rivals to be Littlewoods, Marks & Spencer and C&A, rather than Woolworth, which (with the exception of the Ladybird label) never became a significant clothing retailer. BHS largely abandoned its earlier emphasis on British goods and started to source merchandise from abroad. In 1960 a Times columnist maintained that: ‘British Home Stores . . . has done more for the garment trade in Hongkong than any other single buyer’.

By 1965 BHS had 87 stores (compared with Woolworth’s 1120, Marks & Spencer’s 240 and Littlewoods’ 70). Around 40 BHS stores had restaurants, where microwave ovens were introduced as early as 1966. This was a progressive company. In the same year, BHS took delivery of an IBM 360 computer which no doubt assisted with stock control. Although expansion continued unabated, the BHS board noted that the planning requirements of local authorities were becoming overly demanding. Negotiations were prolonged and difficult, delaying projects. BHS, like many other retailers, began to take ready-made units in speculative developments, such as a parade on St Stephen’s Street, Norwich, built by Norwich Union in 1963. The office tower over this store was not added until 1972.

Arguably the best building erected by BHS, certainly in the post-war period, was its store on Princes Street in Edinburgh. This occupied the site of an imposing 19th-century insurance office, acquired in 1963. The store was designed in 1965 by Kenneth Graham of Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners as part of a scheme to create an elevated walkway along Princes Street, raised above the traffic. Although several buildings – referred to as the Princes Street Panel Buildings – were erected to this concept, it was eventually abandoned. Fragments of similar schemes survive in other cities, such as Sheffield and Bristol. Inside, the Edinburgh store – completed in 1967 – had three sales floors and differed from most other BHS branches by having staircases and escalators grouped in a central position rather than located to the sides of the sales floors. Robert Matthew, Johnson-Marshall & Partners went on to design the BHS store on Market Street and Union Street in Aberdeen. Like Edinburgh, this had boxy projecting window bays.

Southend in 1999

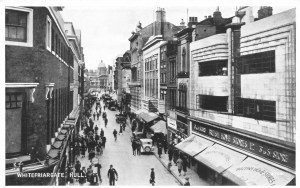

Amongst other new stores of the late 1960s were (third list alert!): Reading (1967), Preston (rebuilt and extended, 1967), Lewisham (1967), Stockport (1967), Newport (Monmouthshire – very large, with 50,000 sq. ft.), Blackburn (1968), Derby (1968), St Helier, Jersey (1968 – the 91st branch), Stockton (1968), Northampton (1968), Southend (1968), Glasgow (Sauchiehall Street, 1969) and Brighton (1969). Between 1967 and 1970 extensions and major improvements included: Watford, Swansea, Wolverhampton, Southampton, West Ealing, Brixton, Liverpool, Darlington, Middleborough, Cardiff (Queen St) and Birmingham. At the end of the decade major stores were under construction in Croydon (Whitgift Centre), Hull and Wood Green.

Newcastle c.2000 (now demolished)

By 1970 BHS had 95 stores, and a decade later this had risen to 125. As in Croydon, branches were increasingly positioned within shopping precincts or malls rather than high streets. New stores of the early 1970s included Bournemouth, Hamilton, Worthing and East Kilbride. In 1971 BHS bought Gamages department store in Romford. Given its name, it would have been astonishing if British Home Stores had survived the Irish ‘troubles’ unscathed. The Belfast store was bombed in 1971 and 1972. In 1973 a fire bomb was discovered in the Wembley branch and another incendiary device was received in post, disguised as a book, at the Marylebone Road branch in London. Despite this, work began in 1973 on a new Dublin branch. Amongst other stores of the mid-to-late 1970s were: Leeds (Bond Street, with 109,000 sq. ft. the largest store in the chain), Stevenage, Grimsby, Aberdeen, Newcastle, Sutton Coldfield, Dundee (Wellgate Centre), Colchester (Lion Walk, 1975), Wandsworth, Bromley, Barnsley, Manchester (1976-8), Peterborough (Queensgate Centre), Milton Keynes and Gravesend (St George’s Centre).

Stevenage (built 1974-75) in 1998

Stevenage, photographed 1 May 2016

BHS maintained a cautious interest in out-of-town shopping through 1970s, biding its time until conditions were more favourable. In 1975 BHS and Sainsbury’s joined forces to create SavaCentre hypermarkets. The first opened in Washington New Town in 1977. SavaCentres were taken over wholly by Sainsbury’s in 1989 and rebranded. By then BHS had started to move into out-of-town shopping malls such as Merry Hill, Dudley. Further afield, foreign franchise stores opened, beginning with Gibraltar in 1985. By 1996 there were 51 franchise stores in 12 different countries, many in the Middle East.

Torquay in 2000

BHS stopped selling food in many stores in the late 1970s, largely as a result of the price war that raged after Tesco abandoned green shield stamps. It was continued at just 56 out of 127 stores. This may have been why Conran Associates were brought in to devise a modern layout, described as ‘open-plan shop-within-a-shop design’, piloted at Harlow, Croydon and Wakefield in 1982. A brief attempt was made to emulate Marks & Spencer’s hugely successful food halls in 1984, but everything changed just two years later.

Canterbury in 1998

In 1986 BHS merged with Mothercare and Habitat to form Sir Terence Conran’s Storehouse group. Conran launched a brighter image for BHS at Kingston-on-Thames, with ‘ash panelling, walkways, bright signposting, and wood and chrome mesh display shelves’. The stores were rebranded as BhS (with a so-called ‘flying h’), though the historic lettering was notably retained in Edinburgh. Conran tried to appeal to younger shoppers and shut remaining BhS food departments. This was a disaster and Conran resigned in 1990.

Bath Homestore in 1998

Harrogate c.2000

In March 2000, Storehouse sold the BhS chain to the entrepreneur Philip Green – who had recently failed in a bid to take over Marks & Spencer. At the time of Green’s takeover there were 155 BhS stores nationally, and the chain had been making losses for some time. Green paid £219 million and converted BhS into a private company.

BhS ‘Homestores’ existed by 1998 and more opened after the acquisition of several Allders stores in 2006. There were 16 of these by 2008, for example in Bath, Chichester and Bromley. From 2009 Green (who was knighted in 2006) began to integrate BhS with his other brands, opening Arcadia concessions in BhS stores. A year later 10 stores (including Harrogate, Guildford and Winchester), were sold to Primark.

Green sold BhS to Retail Acquisitions Ltd in 2015 for a nominal sum of £1. At that time Food Stores were being reintroduced on a trial basis, and Retail Acquisitions subsequently decided to invest effort in building up this aspect of this business. It was also announced in 2015 that the company might have to close or downsize 52 of its 171 stores, and indeed, several high-profile branches (including Fosse Park outside Leicester, Southampton and Carlisle) subsequently closed – by April/May 2016 there were 164 branches of BHS: four in Northern Ireland, 16 in Scotland and the remainder in England.

A deficit in the pension scheme was revealed in March 2016, and the company threatened to close up to 50-60 stores unless its landlords would agree to rent reductions. BHS subsequently gained a brief reprieve. This merely delayed the inevitable, however, and BHS entered administration on 25 April 2016. On 2 June the administrators announced that they had been unable to find a buyer for the business, and that the stores would close. It was further announced on 23 July – amidst a furore over the role played by Sir Philip Green in the company’s demise – that the final store closures would be implemented by 20 August 2016.

Southport in 1999

Continue reading →